IEEE OES Plastics in the Oceans Initiative |

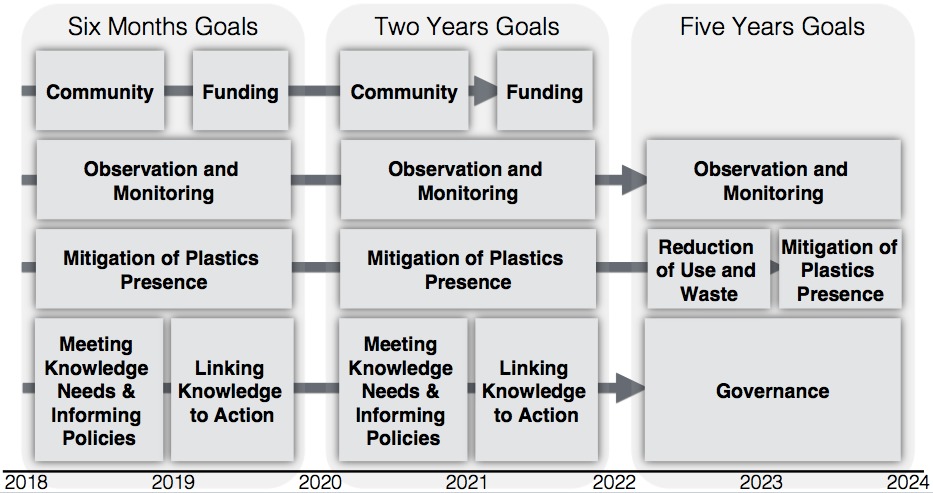

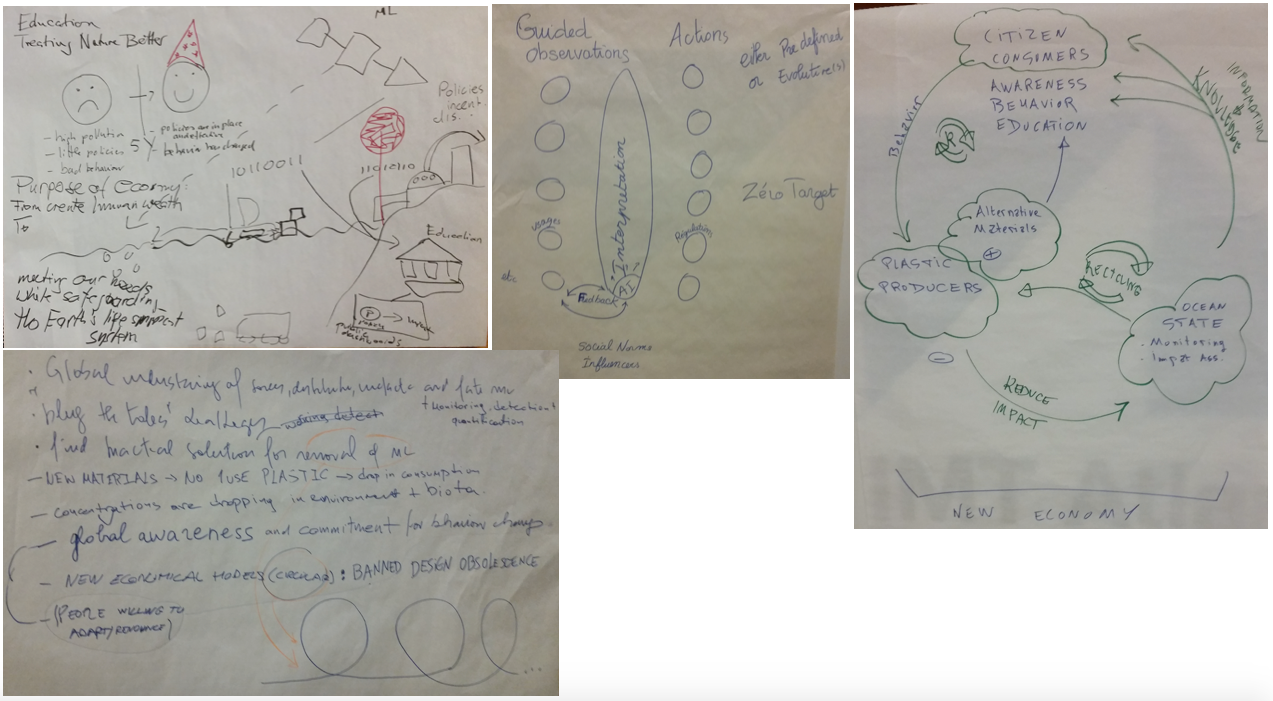

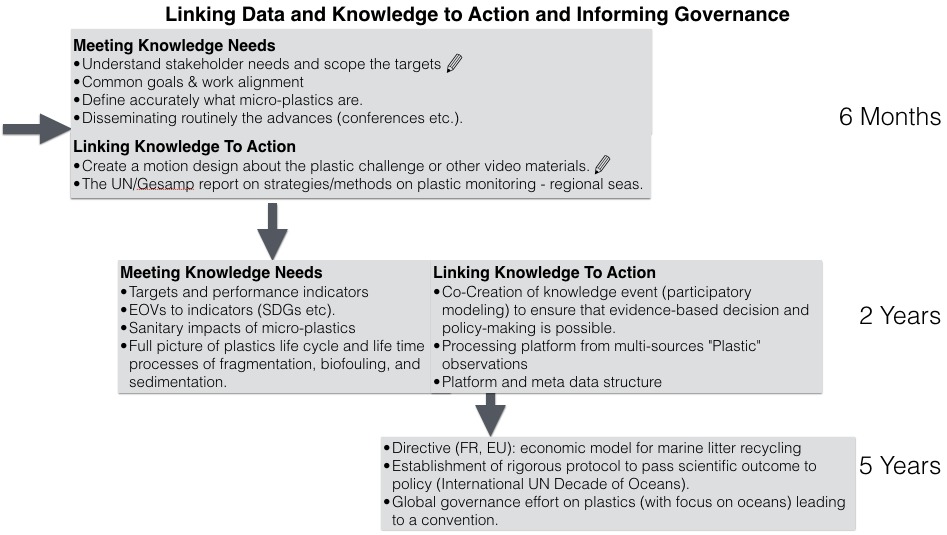

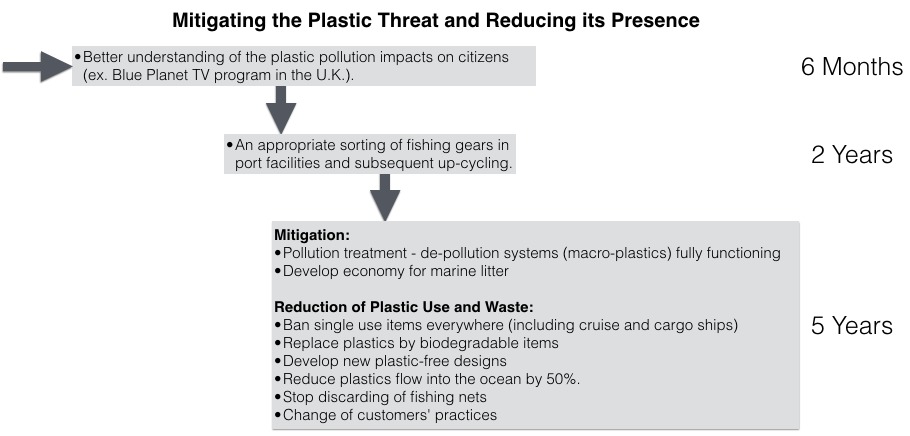

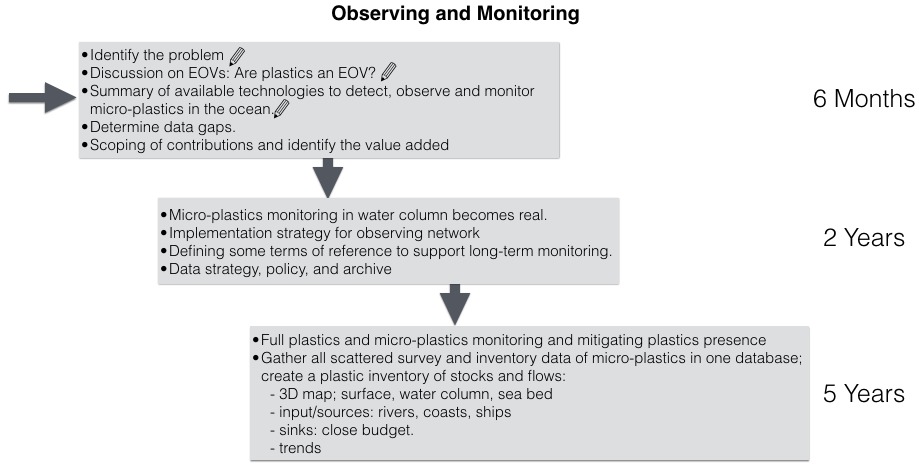

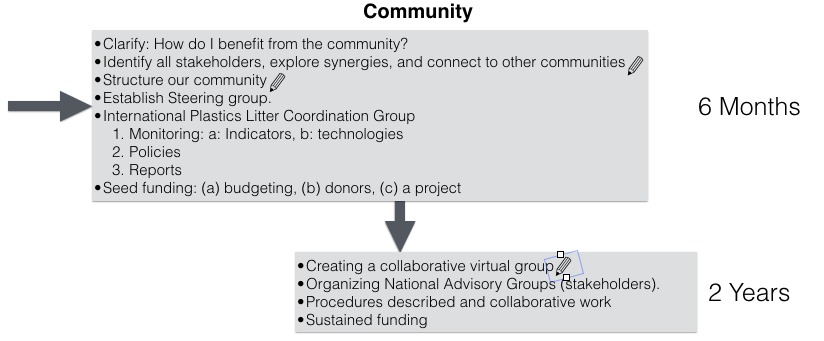

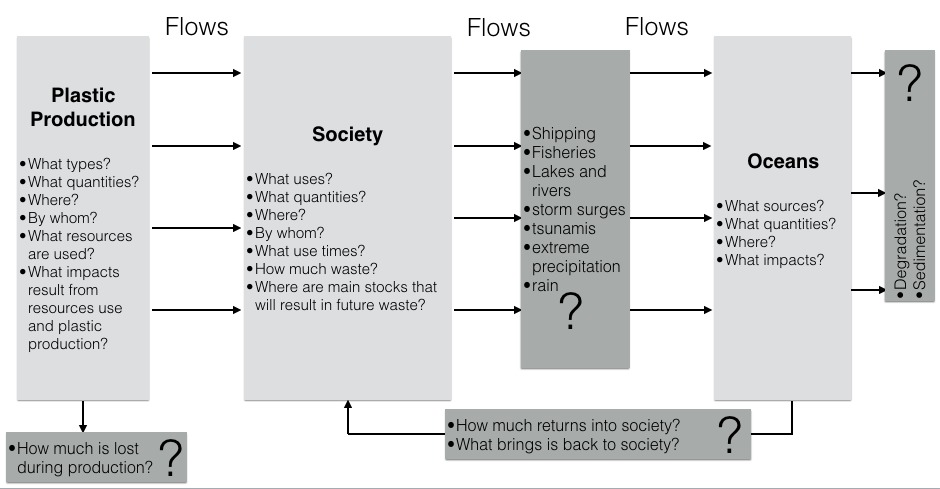

The Road MapEdited by Hans-Peter Plag The road map of the IEEE OES Plastics in the Ocean Initiative aims to organize the work of the Initiative towards the overarching goal of supporting society in efforts to tackle the challenge of ocean plastics through evidence and knowledge-based decision and policy making. The road map lays out goals that need to be reached in order to make progress towards a vision of an ocean with significantly reduced plastics and, more generally marine debris. The road map includes six months, two years, and five years goals. These goals can be grouped under four main themes: (1) linking data and knowledge to actions and informing governance; (2) mitigation of plastics and reducing its presence; (3) observation and monitoring; (4) community building (Figure 1).  Figure 1: The structure of the goals and activities that were identified for the road map during the 2018 Workshop. Note that an interactive version of the figure is available in the workspace. Long-Term VisionDuring the 2019 Workshop in Brest, both the long-term vision and the goals for the next six months were considered in more detail. Four groups developed vision graphics and in a subsequent plenary discussion, one of those four was accepted as the guiding vision by the plenary (Figure 2). This vision is based on a new economy, in which plastics producers make an effort to develop alternative materials and reduce the impacts of plastics on the ocean. Recycling of plastics that is already in the ocean would reduce the amount of marine litter. The knowledge about the ocean state resulting from comprehensive monitoring and impact assessments combined with education would contribute to higher awareness among citizens and consumers and lead to a change in behavior. One of the graphics (upper left in Figure 2) emphasized the need for education that would lead to people in general “treating nature better.” A general change in the purpose of the mainstream economic system from solely focusing on creating human wealth to one that would meet our needs while safeguarding the Earth's life-support system was considered a core transition to address the challenge of plastic pollution. Such a change would improve the current situation characterized by “high pollution, little policies, bad behaviour” to a more desirable situation of “policies are in place and effective; behaviour has changed.” Comprehensive monotoring of marine litter including plastics would provide urgently needed information for policy making, and controlling the flows of plastic from land into the ocean would be a priority everywhere.  Figure 2: Vision graphics produced at the 2019 Brest workshop. The graphics in the upper right corner was selected as the consensus one. Linking Data and Knowledge to Actions and Informing GovernanceThe long-term (5 years) goals under this theme relate to regional and global policies and conventions that would facilitate the recycling of marine litter and strongly reduce the flow of plastics from land into the ocean (Figure 3). A directive at European level in support of an economic model for marine litter recycling is already under discussion. Efforts to reach a convention on plastics with a focus on the oceans was identified as an important goal. To achieve this, it would be important to establish a rigorous protocol to pass scientific outcomes to policy making, and the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development as a framework for the development of such a protocol. At the two-years time scale, a review of the targets and performance indicators should be carried out. Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs) for indicators related to the SDGs and other goals need to be identified. A full picture of the plastics use and life cycle, including the processes of fragmentation, biofouling and sedimentation needs to be constructed. In terms of linking knowledge to action, events for the co-creation of knowledge are necessary to ensure evidence-based decision and policy-making. Participatory modeling efforts could facilitate this co-creation of knowledge. A platform that would link observations and knowledge to societal agents needs to be developed. This platform would allow to process observations from a broad range of sources. The specification of a metadata structure would be necessary. In the short term (six months), it will be important to full map the decision space around plastic in the ocean and marine litter in general. This will help understanding the stakeholder needs in terms of data, information and knowledge, and with this understanding, a scoping of targets for the action can be carried out. The mapping of the decision space is part of the case study that is being carried out. A community effort can then lead to common goals and the alignment of work in different groups. The dissemination of the community advances through relevant conferences, the community web space, media outlets, and publications has to become a permanent effort of the community. The creation of a motion design or other videos illustrating the challenge of plastics in the ocean and the contribution the community is making is already under way. Link of this community to GESAMP and relevant UN activities need to be explored and extended. In particular, the GESAMP “Guidelines for the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter in the Ocean” (GESAMP, 2019) have to be considered.  Figure 3: Road map for the theme Linking Data and Knowledge to Actions and Informing Governance. Mitigating the Plastic Threat and Reducing its PresenceFor mitigation of the plastic pollution, the long-term goals (5 years) aim at a system for the de-pollution of the ocean particularly focusing on macro-plastics being in place and fully functional. The de-pollution would be easiest to achieve in an economy for the use of marine litter as a resource. Activities that make an effort to turn “waste to value” (see e.g., Daugherty, 2020; Ablordeppey, 2019). A significant reduction of use of plastics and of plastic waste are considered mandatory for any successful limitation of ocean plastics. In the long-term, a general ban of single-use plastic items appears necessary. This would also include cruise and cargo ships. As far as possible, plastics need to be replaced by biodegradable materials, although more research is needed to ensure that these biodegradable materials do not have strong environmental impacts. New designs also need to focus on avoind plastics as material. A significant change in customer and consumer behavior and practices also is a goal to be achieved on a 5-year time scale. The flow of plastics into the ocean needs to be reduced close to zero, and a 50% reduction should be achieved with 5 years. Importantly, since left-behind fishing gear makes a significant contribution to marine litter including micro-plastics (Xue et al., 2020) a goal is to stop the discarding of fishing gear. This is consistent with goals of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. The actions on a 2-year time scale identified so far in the road map are limited to efforts towards appropriate sorting of fishing gears in port facilities and efforts to reuse gear or up-cycle any discarded gear. The case study may result in more targets to be included here. In the short-term, a better understanding is needed of the impacts of plastic in the ocean on humans. Importantly, how does plastic enter and accumulate in the marine food chain and link into food for humans?  Figure 4: Road map for the theme Mitigation of the Plastic Threat and Reducing its Presence Observation and MonitoringAlthough the societal knowledge needs arising from policy and decision making related to ocean plastic and marine litter in general have not been full explored, it is clear that comprehensive monitoring of plastic and marine litter presences in the ocean is necessary if these knowledge needs are to be met. The 5-year goal of a comprehensive plastic and micro-plastic monitoring acknowledges this requirement. The on-going efforts of developing the integrated marine debris observing system (Maximenko et al., 2019) is an important step toward this goal. A gathering of the currently widely scattered survey and inventory data of plastics and micro-plastic in one database is seen as an important step in this direction. This database should provide an inventory of all plastic stocks and flows, including the sources and sinks, and it should be possble to assess trends based on the available information. On a 2-year time scale, having the technology and processes for the monitoring of mico-plastic in the water column is considered an important target. The implementation strategy for the observing network needs to be available, and terms of reference in support of long-term monitoring need to be agreed upon. In the short term, a shared understanding of the problem is necessary, and the case study should generate this. There is a need to discuss to what extent the various forms of plastic in the ocean should be considered as Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs). A summary is needed of the available technologies to detect and monitor plastics in the ocean, and this summary is already available in the White Paper on “A Global Platform for Monitoring Marine Litter and Informing Action” (Smail et al., 2020). This White Paper also identifies some of the data gaps. The case study is expected to reveal more data and knowledge gaps, and the case study also will scope the contribution that could be made by the community and the value that could be added.  Figure 5: Road map for the theme Observation and Monitoring. Community BuildingFor the community building, the road map includes 6 months goals and 2 years goals (see Figure 6). The community to be brought together consists of those stakeholders interested in tackling the marine plastic litter challenge. A first step is a mapping of all stakeholders that need to be considered in collaborative efforts. It is important to establish a steering group that can direct and guide the community-building efforts. Those stakeholders with high interests and authorities to tackle the problem should be represented in the steering group. Efforts should be made to identify funding opportunities for the efforts and to develop a project plan. On a 2-year time scale, a collaborative virtual group should be established. This group could be based on a federation of national advisory groups. Procedures facilitating the collaborative work should be described. Efforts to ensure sustained funding should be made.  Figure 6: Road map for the theme Community Building. Main QuestionsFigure 7 summarizes the main questions identified so far to be addressed by the community. Many of the questions aim to quantify the flows between the different plastic stocks in society and in the environment. Earth observations can, and must, contribute to the quantification of the stocks of plastic in the different environmental subsystems. Preliminary studies show that there are many large uncertainties concerning the stocks and flows of plastic through society from production to use and waste, and from waste back to reuse or into the environment. It may be important to compile a comprehensive and integrated database capturing all flows and stocks, and to develop a stock and flow model that can be used to identify data gaps as well as inconsistencies in the data.  Figure 7: Main knowledge gaps concerning the flow of plastic into the ocean and the fate and impacts of plastic in the ocean. ReferencesAblordeppey, S. D., 2019. Plastic waste or value?. Graphic Online, html. Daugherty, S, 2020. How local teamwork is transforming plastic waste into value. National Geographic, html. GESAMP, 2019. Guidelines or the monitoring and assessment of plastic litter and microplastics in the ocean (Kershaw P.J., Turra A. and Galgani F. editors), (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP/ISA Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection). Rep. Stud. GESAMP No. 99, 130p, html. Maximenko, N., Corradi, P., Law, K.L., Sebille, E.V., Garaba, S.P., Lampitt, R.S., Galgani, F., Martinez-Vicente, V., Goddijn-Murphy, L., Veiga, J.M., Thompson, R.C., Maes, C., Moller, D., Löscher, C.R., Addamo, A.M., Lamson, M., Centurioni, L.R., Posth, N., Lumpkin, R., Vinci, M., Martins, A.M., Pieper, C.D., Isobe, A., Hanke, G., Edwards, M., Chubarenko, I.P., Rodriguez, E., Aliani, S., Arias, M., Asner, G.P., Brosich, A., Carlton, J.T., Chao, Y., Cook, A.-M., Cundy, A., Galloway, T.S., Giorgetti, A., Goni, G.J., Guichoux, Y., Hardesty, B.D., Holdsworth, N., Lebreton, L., Leslie, H.A., Macadam-Somer, I., Mace, T., Manuel, M., Marsh, R., Martinez, E., Mayor, D., Le Moigne, M., Jack, M.E.M., Mowlem, M.C., Obbard, R.W., Pabortsava, K., Robberson, B., Rotaru, A.-E., Spedicato, M.T., Thiel, M., Turra, A., Wilcox, C., 2019. Towards the integrated marine debris observing system. Front. Mar. Sci., 6. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00447. Smail, E., Campbell, J., Takaki, D., Plag, H.-P., Garello, R., Djavidnia, S., Moutinho, J., El Serafy, G., Giorgetti, A., Vinci, M., Jack, M E. M., Larkin, K., Wright, D. J., Galgani, F., Topouzelis, K., Bernard, S., Bowser, A., Colangeli, G., Pendleton, L., Segui, L. M., Milà i Canals, L., Simpson, M., Marino, A., Zabaleta, I., Heron, M., 2020. A Global Platform for Monitoring Marine Litter and Informing Action. Draft White Paper, UNEP. Xue, B., Zhang, L., Li, R., Wang, Y., Guo, J., Yu, K., and Wang, S., 2020. Underestimated Microplastic Pollution Derived from Fishery Activities and “Hidden” in Deep Sediment. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(4), 2210-2217. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b04850. |

This Initiative is sponsored by:

|

|