Marine Debris Indicators: What’s Next?An IEEE OES event

|

|

|

THE WORKSHOP

The workshop on “Marine Debris Indicators: What is Next?” was held on December 16-18, 2019 in Brest, France. Building on a first workshop held in November 2018 also in Brest on “Technologies for Observing and Monitoring Plastics in the Oceans” this second workshop aimed to strengthen the link between observation, extracted information, and decision and policy making. The workshop also provided a platform for the further development of a community focusing on monitoring and measuring of marine debris.

Recognizing the UN targets for ocean plastic and related indicators, the second Marine Litter workshop brought together experts on observations and monitoring of marine debris and plastics with decision and policy makers in need of comprehensive information on this challenge. Focusing on targets and performance indicators, the goal was to converge towards common best practices and potential standards. Bringing in relevant stakeholders, the workshop also fostered collaborative networks to ensure that evidence-based decision and policy-making are possible.

WORKSHOP BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVES, AND SCOPE

The Challenge

Marine debris is of growing global concern. Increasing material consumption and plastic production contribute to more marine litter and have resulted in estimates that over 8 million tonnes of plastic leak into the ocean each year. While quantitative information on production and use of plastics is to a large extent available, the fate of plastics discarded or leaked into the environment is highly uncertain. In particular, knowledge of how much plastic at different scales down to micro and nano levels reaches the ocean and the trajectories of the plastic in the ocean remain poorly known.

The Earth observation community so far has not managed to establish a global tracking and information system that would provide quantitative information on where and how plastics move in the ocean and allow the identification of the points where marine plastic pollution could be reduced most effectively. A necessary first step in addressing marine litter includes establishing a knowledge base for the amount of marine litter that has entered the ocean. In order to establish this knowledge base, the right actors need to be involved and they require a global platform to coordinate monitoring marine litter and informing action.

Pre-Workshop Activities

The goal of the November 2018 workshop on “Technologies for Observing and Monitoring Plastics in the Oceans” was to identify future technology initiatives able to address the mounting global marine debris with particular focus on plastics in the ocean. The workshop addressed the interest of the UN Environment Program in finding support for their efforts to develop the methodology for monitoring marine debris indicators, in particular the Indicator 14.1.1 “Index of coastal eutrophication and floating plastic debris density” of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” The major outcome of this workshop was a draft road map with a set of activities and goals for six months, two years and 5 years, which provided an initial road map (see Garello et al., 2019).

At a Town Hall meeting at the OCEANS 2019 conference in Seattle on October 29, 2019, the challenge of marine debris, in particular, plastics, was presented and approaches to monitoring indicators were considered. The discussion touched upon a wide range of topics including the societal challenge of reducing the use of plastics in an economy that has developed a high dependency on plastics, detecting and monitoring plastics in the environment and in the oceans, understanding the impacts of plastics on the biosphere including humans, and approaches to a better linking of science and policy making.

Both event provided valuable input for working out the scope and objectives of the second workshop program and the development of the program.

Workshop Scope and Objectives

Building on the recommendations and draft road map of the 2018 Workshop, the main goals for the workshop was to further develop a community of stakeholders around marine debris and to further detail the road map towards a joint goal. The overarching goal for this community is to achieve a comprehensive description of observation means (underwater, satellite-borne, in situ, crowd sourcing, Big Data analyses) and assess their technological readiness, as well as, their availability for relevant indicators, including the SDG Indicator 14.1.1, and to ensure that a range of emerging efforts to address the global challenge of marine debris can be based on sufficient observational evidence.

The workshop explored the potential for a platform linking the data to actions and develop an implementation strategy for observing networks and modeling platforms to support co-creation of knowledge needed by those addressing all aspects of marine debris.

PARTICIPATION

The workshop brought together a broad range of stakeholders from Earth observation communities, research communities assessing the intermediate and long-term impacts of marine debris, United Nations and national agencies engaged in making progress towards SDG 14, businesses tackling various aspects of the problem of marine debris, as well as, experts working at the interfaces between these communities with the goal to ensure that knowledge required for policy making is created, accessible and usable.

More than 50 in-person and remote participants from twelve countries represented a wide range of stakeholders from all societal sectors.

WORKSHOP APPROACH AND FORMAT

The first part of the workshop included several sessions with invited presentations and brief discussions. This part aimed at reviewing the current state in monitoring marine debris and relevant modeling, and aimed at an overview of the knowledge needs for societal decision making on mitigating the threat marine debris poses to the ocean and human beings. See the next section for more details.

The second part took a participatory approach in which the participants worked together to improve the draft road map that resulted from the first workshop in 2018. Initially, several groups collected sets of relevant terms and developed graphics of their vision for the next five years. Then the plenary agreed on a common vision, which provided a basis for the work on elements of the road map with a particular focus on the elements to be implemented during the six months leading up to the next workshop in June 2020 in Lisbon, Portugal. During the final session, input for a case study on “Reducing Plastics in the Ocean within a Growing Global Economy: Understanding the Information Needs to Support Interventions” was collected in a participatory effort.

WORKSHOP PROGRAM AND DELIBERATIONS

Session 1: Speed Meeting

During this session, all participants introduced themselves to the plenary, with most of the participants showing up to three slides. The first slide introduced the participant, the second slide gave an overview of the interests of the participant, and the third slide informed about the participant's expectations to the workshop by providing information on ambitions, ideas, contributions and networks.

The participants' interest covered a wide range of research, professional and societal issues. Most of the participants expected to increase their knowledge about different aspects of marine debris and plastics in the ocean, and many of them expected to extend their network and develop opportunities for collaborations or to identify opportunities to raise awareness of the challenges and threats.

Session 2: State of the Art and Emerging Opportunities

Rene Garello gave an overview of the challenge with marine debris indicators and the necessary next steps, which included an introduction to the IEEE OES Initiative on plastics in the ocean. Hans-Peter Plag summarized the road map developed during the first workshop in 2018, which included six months, two years, and five years goals. These goals could be grouped under four main themes: community building, observation and monitoring, mitigation plastics and reducing its presence, linking data and knowledge to actions and informing governance. Jillian Campbell introduced the participants to the reporting process for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and discussed the Indicator 14.1.1 for SDG 14 “Life below Water” in detail. This indicator is associated with Target 14.1 “By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution” and aims at an index of coastal eutrophication as well as information on plastic debris density. Jillian Campbell emphasized the need to integrate traditional Earth observations with new data from, e.g., citizen scientists and crowd sourcing. Emily Smail provided thoughts on progress towards a global platform for monitoring and marine litter in support of informing actions. She summarized a white paper under development for UNEP, which discusses the state of the different observation and monitoring technologies and methods, and considers the alternatives of integrated platforms versus digital ecosystems. The session concluded by L. Pendleton introducing the participants to the Ocean Data Foundation. Based on the necessity for a sustainable use of the ocean of opening the bulk of ocean data and making it available for a broad use by many societal agents, this foundation is developing the Ocean Data Platform (ODP) as “an open and collaborative platform that harnesses the power of data liberation and contextualization for the people.”

Session 3: Monitoring: From Sensors to Indicators and Policy

Francois Galgani discussed challenges in the development of indicators for marine debris. Pier Luigi Buttigieg emphasized the needed to integrate marine debris knowledge into robust, open, and collaborative digital resources, which would help distributed systems to be independent but interoperable resources. He introduced the SDGIO, which is based on a common, human- and machine-readable map of SDG-related knowledge available to all. It uses standard semantic web technologies and part of a federation of other ontologies, and it has an open editorial policy with all being invited to contribute, co-design, and co-develop SDGIO. He underlined that a carefully curated and quality-controlled semantic layer would be key to interoperability between marine debris databases and other knowledge repositories. Hans-Peter Plag suggested a shift in focus from “analysis-ready data” to “use-ready knowledge.” Picking up the recent proposal for a digital ecosystem, he introduced “Intelligent Semantic Data Agents” (ISDAs)that would represent digital data and knowledge objects and be able to provide access to these objects, answer question about the objects, receive feedback from users, and interact with other ISDAs. Utilizing extensive graph data, the ISDAs would be able to discover potential users of their objects, thus facilitating a transition from users discovering data to data and knowledge discovering users. Artur Palazc considered marine debris as a Human Pressure Essential Ocean Variable (EOV), and he reported on initiatives to establish an Integrated Marine Debris Observing System (IMDOS). He pointed out that efforts to develop a marine debris EOV specification sheet are underway. In a second presentation, Pier Luigi Buttigieg contemplated whether best practices should be collected in a single repository or be represented in a distributed network. Here a methodology that has repeatedly produced superior results relative to other methodologies with the same objective is considered a best practice. He pointed out that, unfortunately, many best practices are not comprehensively documented and often difficult to find. The Ocean Best Practices System (OBPS) provides a single-system approach to making best practices available. He concluded that the single-system and distributed network approaches both could work, but distributed systems would have to be truly interoperable and federated.

Session 4: Observations and Models for Marine Debris Indicators

Dimitris Papageorgiou reported on projects that explore technologies and methods for the detection of floating plastic debris. In these projects, targets for the detection are placed in the ocean, and combinations of drone and satellite images are utilized to detect these target. As a result, a number of factor affecting the detection capability were identified including plastic debris abundance fraction, sunglint, bottom reflectance, whitewater, cloud shadows, and a number of technical parameters. Steffen Fritz discussed the role of citizen science in observing marine debris. He pointed out that citizen science can provide valuable information on the distribution of marine litter especially in remote areas, and citizen engagement in beach litter projects results in behavioral changes. He emphasized that focusing only on cleaning up marine debris will not reduce the marine litter added to the ocean continuously. Using the Picture Pile tool to sort piles of pictures, citizens can be engaged in a number of topics, including marine debris. He concluded his presentation by pointing the participants to Earth Challenge 2020, which is a citizen science initiative with the goal of engaging millions of global citizens. Joan Mira Veiga considered many aspects of plastics from the source to the sea and emphasized the need for a transition of the current linear economy that produces increasing amounts plastics that after use end up as waste in the environment to a circular economy that reuses all resources in waste and thus has minimal leakage of waste back into the environment. She underlined the need of assessments that inform decision making and recommended that the "source-to-sea" approach includes upstream sources and pathways.

In the second part of this session, Julien Chupin introduced companion modeling and discussed a collaborative approach to reducing marine debris. Using an example of a companion modeling on Cameron, he illustrated how change can be driven through a collective process. This part of the session was preparing the participants for a participatory effort in the afternoon session to further develop the draft road map. Julien Chupin started by presented the hypothesis "you want to eradicate marine debris" as the main consortium vision. In order define an actionable road map there is a need to define a problem to adress. For this purpose a first step is to clarify the Actors, Resources, and Dynamics connected to the marine debris system. The participants were asked to provide input for each of them.

Input from four groups for relevant actors, required resources, and dynamics to be considered in eradicating marine debris.

Referring to the road map drafted during the first workshop, Julien Chupin asked which problems, related to the actors and ressources previously identified, the road map is addressing. In a summary, the key messages learned so far as well as the points to be further explored were collected and evaluated. Among the messages learned were:

- holistic understanding is key to targeted actions and real impact (e.g. what are the actors problems?);

- The anaylysis of the system, through scenarios and serious game, allow to identify targeted action;

- What are the limits of knowledge? Minimum level to be able to step up and act. If we don't others will and potentially bring bias to the decisions.

- Successful participatory modelling to solve complex problems in a collaborative manner depends strongly on who is in the room, on getting the right actors to sit at the table.

- the objectives, analyses, proposed solutions have to be discussed within an interactive approach with others;

- playing games with concerned people;

- Our/the road map has to be efficiently pushed toward game changing actors;

- Produce and disseminate accurate and relevant information/research to public and interested parties,

- It is quite easy to produce a road map and to convince decision makers, but very difficult to apply the road map to induce the change.

Points to be further explored grouped into strategy, engaging stakeholders, methods, polities, and research:

- Strategy:

- Define boundaries, and audience as starting point;

- Align activities and identify targets to impact with tailored communications;

- Solving the marine litter problem is a wicked problem that needs both small and big system changes from local to global;

- an efficient communication plan;

- definition of local solutions;

- how to translate ideas generated in the workshop into concrete actions?

- engaging stakeholders:

- Comprehensive participation is key to understand complex problems and to support actions;

- How can you make people pay attention to problems they think they are not part of?

- Way forward: communicate road map in right form.

- Method:

- How do you convert the knowledge of the actors, problems, and dynamics into an actual game? How do you test that the game will work?

- Policies:

- How does the political decision process work?

- How can we involve key decision makers in participatory approaches? We need that!

- Transfer of the message to policy making and citizens.

- Research:

- Impacts of plastic particles in ocean ecosystems: How many? Where? On what?

- Better understand the life cycle of plastic.

- Models of decision making process — to have support also from data and AI.

- Consultancy

Main lessons learned and points that need to be explored further.

Session 5: Posters

The poster session feature five posters addressing a range of relevant issues. Maes et al. revisited the convergence of surface drift in the South Pacific convergence zone and confirmed that there is a surface convergence into five main accumulation zones. Jacquin et al. reported research on the biodegradation in the marine environment of wadded sticks resulting from domestic use. Simpson et al. informed about progress in addressing the challenges and utilizing the opportunities in using Sentinel-1 SAR images for the monitoring of plastic in the ocean. Martin et al. outlined a modeling project focusing on the use trajectory of plastics with the goal to trace back ocean plastic to the origin. Jone at al. emphasized the growing risk associated with large increases in marine debris resulting from the rapidly growing urban coasts exposed to many ocean-related hazards such as tsunamis, storm surges, cyclones, and sea level rise, with the probability density function for many of these hazards changing due to climate change and ocean heating.

Session 6: Connecting Data to Actions

Gilles Ollier discussed the EU policy and actions on reducing marine litters including plastic debris, and he emphasized that there are many relevant policies and initiatives, including among others the efforts to make progress towards a circular economy. With respect to plastics, the “European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy” provides focused international actions, aims to improve reuse and recycling, as well as, curbing marine litter, and promotes investigations of circular solutions. He outlined many funding opportunities and pilot actions for the removal of marine litter. Importantly, there is an ongoing effort to achieve a common European framework that harmonizes procedures for plastic pollution monitoring and he mentioned the efforts towards the IMDOS. Francois Galgani provided an overview of the work carried out by the Technical Group on Marine Litter (TGML) under the Horizon Europe Framework.

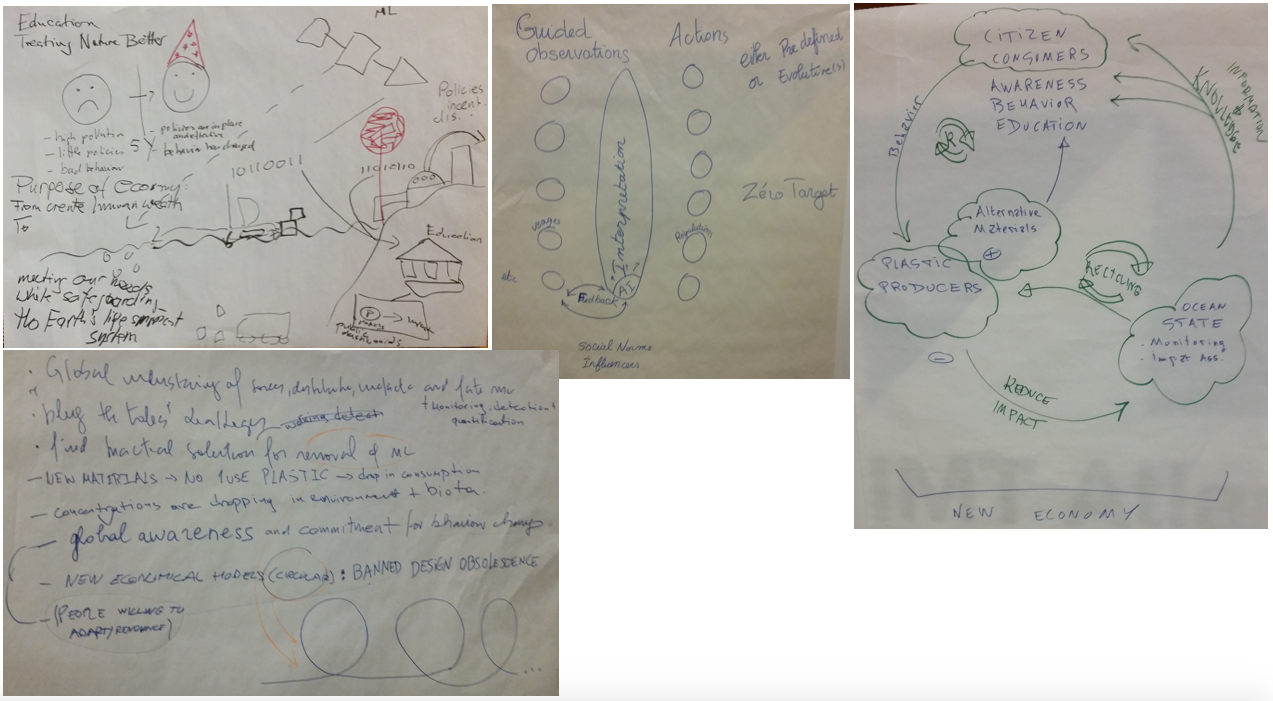

The second part of this session focused on the further development of the draft road map. This part was moderated by Julien Chupin. A first step in this process is to agree on a common goal. For that, four groups were asked each to develop a graphical vision for 2025. The groups presented their visions to the plenary and an open voting was used to determine the vision with the largest support. This vision was then enriched in plenary, each participant having the opportunity to contribute to it.

Vision graphics developed by four groups. The vision on the upper right was accepted as the guiding vision by the plenary.

Session 7: Road Map

|

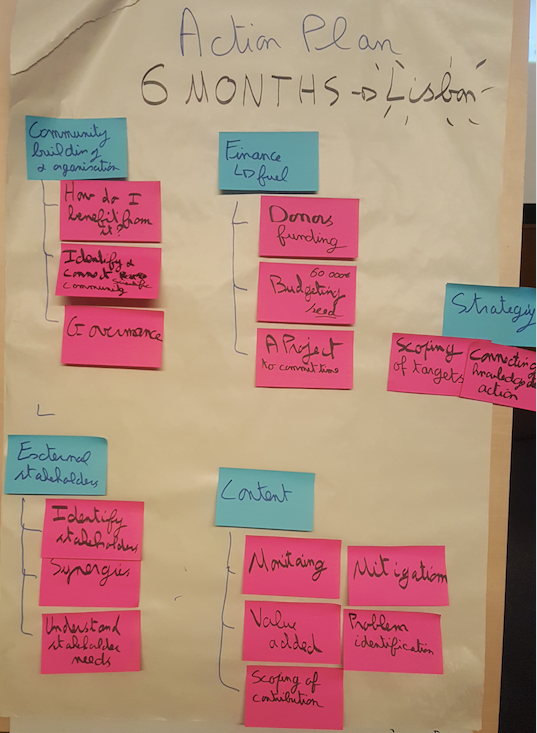

The participants worked collaboratively on the further development of the road map. Main focus was on the next six months. For the next six months prior to the next workshop to be held in Lisbon, Portugal, the following points were collected:

|

The action plan for the next six months prior to the third workshop to be held in June 2020 in Lisbon, Portugal. |

Session 8: Working Groups - Road Map

The participants decided to continue as plenary and to concentrate on the development of a case study that would focus the emerging community on a joint project. The topic of the case study emerged as “Reducing Plastics in the Ocean within a Growing Global Economy: Understanding the Data Needs to Inform Actions.”

An interactive collaborative effort was made to solicit from the participants input for the case study.

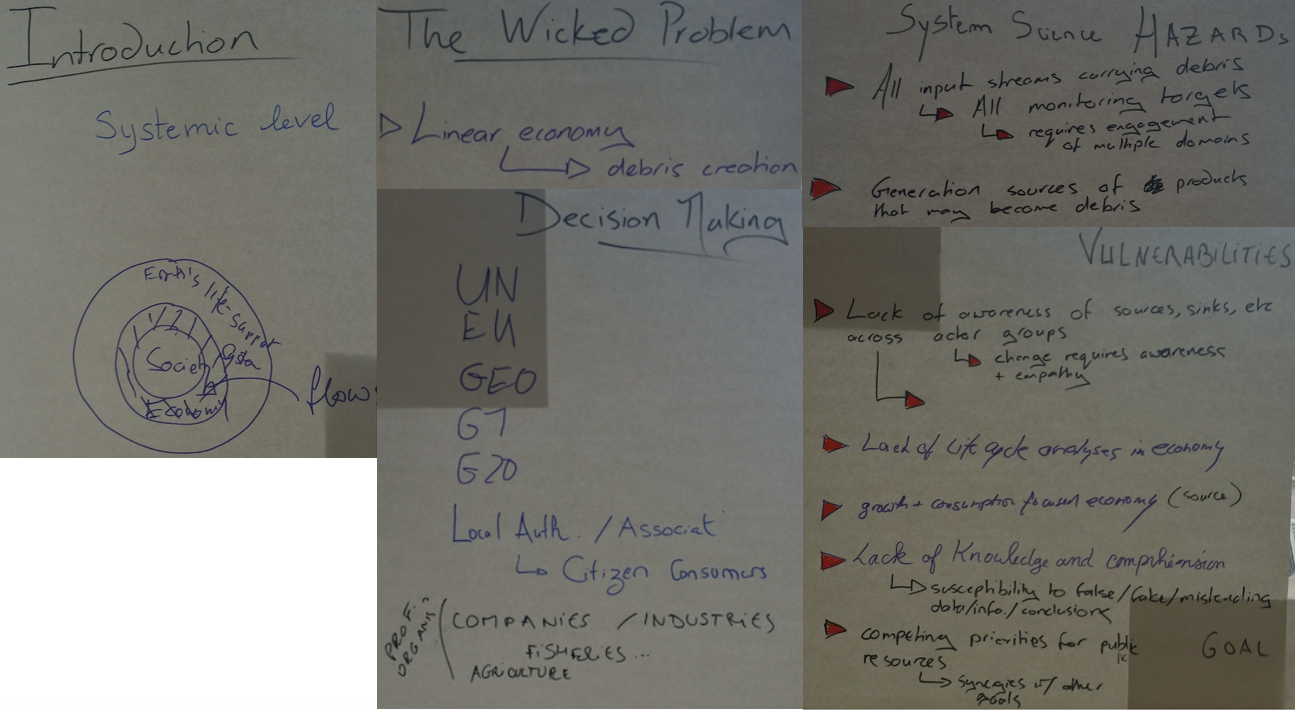

Introduction

It was emphasized that the case study needs to be carried out at the systemic level considering all flows of plastic through society and economy into the Earth's life support system and back to human society. The focus on flows pointed towards the development of a stock and flow model for a comprehensive use trajectories of plastic from the source to the environment and throughout the environment. Here the term "use trajectory" is preferred over "use cycle" or "life cycle" because to the linear nature of the mainstream economic model, which in human-relevant times results in more or less linear trajectories from the origin of plastic to the eventual deposition of it in parts of the environment.

Input for the introduction, the wicked problem, the decision space, and the systems science part collected during the collaborative session.

Wicked Problem

Among the ten criteria that define wicked problems, one is the fact that the problem definition depends on the desired solution (Rittel and Webber, 1973). Thus, the goal statement “Reducing Plastics in the Ocean within a Growing Global Economy” defines the wicked problem. The participants agreed that the community is in no position to address this problem, and it was agreed to focus on the data and information needs addressing this problem generates.

It was pointed out that a linear economy is the root cause for the generation of large amounts of debris that ends up in the ocean. Only if a transition to a more circular economy can be made is a significant reduction of new debris likely.

Conceptual Model

There was considerable discussion that a conceptual model needs to be developed that captures all relevant elements in the use trajectories of plastics and allows for an assessment of mass balance. Based on this conceptual model, a causal loop diagram should be compiled, which would provide the basis for a comprehensive stock and flow model.

Decision Space

In the discussion of the decision space, it was emphasized that a list of the relevant stakeholders needs to be compiled with sufficient information on their interests, impacts, resources, contribution to generating debris, potential contributions to reducing debris, as well as policy and decision making authorities. Those stakeholders that could generate data and information should also be included. The initial list included the UN, EU, GEO, G7, G20, local authorities, citizens, consumers, professional organizations, companies, industries, fisheries, and agriculture.

Hazards

Focusing on the hazards posed to the ocean, all input streams carrying debris were listed first. All of them have to be monitoring targets, and this requires engagement of multiple domains.

The sources where products originate from that may become debris also need to be identified and assessed.

Vulnerabilities

The discussion of vulnerabilities focused more on the socio-economic part of the global system and characteristics that hamper efforts to reduce sources of debris. The lack of awareness of sources and sinks across actor groups was mentioned as a main vulnerability, and a change of awareness and empathy was considered necessary to reduce this vulnerability. The lack of life cycle analyses in economy and the requirement of the mainstream economic model to create economic growth through increased consumption are also among the vulnerabilities identified. The lack of knowledge and comprehension that many stakeholders exhibit makes them vulnerable to false, fake, and misleading data, information, and conclusions. Competing priorities limit access to public resources needed to address the problem of debris, and synergies with other pools need to be explored.

Foresight

The conversation abut the spectrum of possible futures was centered around the desirable future. In this desirable future, stakeholders in the public and sciences and those engaged in policy making have access to understandable monitoring and observation information, which allows them to better understand their roles in potential solutions. This could be initiated with a CHM to survey and align activities.

In this future, a mass balance framework is available that conveys interconnectivity by capturing all stocks and flows and all sources and sinks. It provides collective information on flows into the system, and the compartments of this framework match the hazards, which provides a basis for mitigation. The flows, hazards, etc. are mapped to the relevant actors, and a dashboard provides targeted interfaces for these actors.

A collective group or body represents the community and links to existing assessments such as UNEP state reports, and SoEuEnv.

Initial rough sketch of a desirable future and interventions that could initiate progress towards this future.

Interventions

The interventions considered focused on transformation knowledge related to the social system. Effects need to be made to create new mentalities and social norms and pressures that are well informed on the impacts of debris as well as the roles of different actors. This should comprise all citizen consumers and reaching there, requires a major education effort.

The ability to detect false information, identify suspect data and conclusions, and allocate trust wisely across all stakeholder groups (in the public, policy making, and science) needs to be fostered. Developing citizen science is considered a valuable avenue towards this goal.

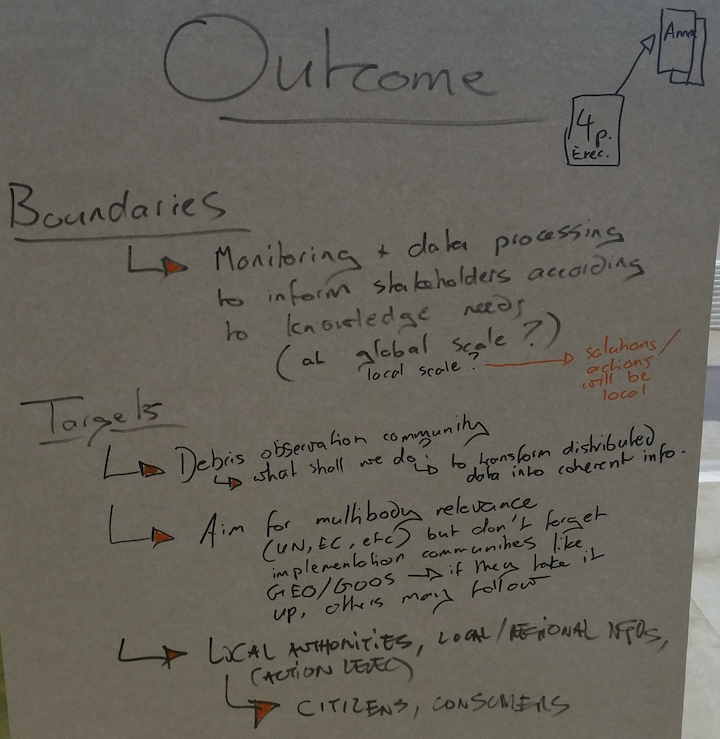

Recommendations

The conversation about potential outcomes and recommendations to be made resulted in inputs related to boundaries and target audiences. Needed outputs included the monitoring and data processing to inform stakeholders according to knowledge needs. It was pointed out that while this is needed at global scale, solutions and actions will often be at local scale with specific knowledge needs.

Targets that should be focused on by the debris observation community included the transformation of distributed data into coherent information. There should be an aim for multi-body relevance (UN, EU, etc.), but implementation communities like GEO and GOOS should not be overlooked, because if these communities achieve this goal, then others will follow.

Local authorities, local and regional NGOs, as well as, citizens and consumers should also be included in the target audiences and their knowledge needs should be considered.

Thoughts on anticipated outcomes collected during the collaborative session.

Session 9: Wrap Up - Conclusions

During the final session, the participants discussed the structure of the workshop report and identified lead authors for the different sections. There was agreement that the next workshop, the 3rd Workshop on plastic and other marine debris would be held in late May 2020 in Lisbon prior to the UN Ocean 2020 meeting.

The road map elements developed for the next six months will provide guidance for the work leading up to this next workshop. In particular, the case study discussed in Session 8 will be developed as much as possible. The next workshop will then provide an opportunity to collaboratively complete this case study.

WORKSHOP OUTCOMES

The first sessions of the workshop provided a good overview of the current status in terms of observing and monitoring plastic and other debris in the ocean, as well as, the linking of information to action.

- There are many efforts under way to bring observation technologies to a high technical readiness level, and a number of promising technologies are either tested or under development.

- Despite these efforts, technologies and methodologies for a comprehensive monitoring of fluxes of debris into the ocean and the movement of debris in the ocean are still limited and there are no standards and best practices for data collection and processing.

- Data on marine debris are coming from a wide range of sources including remote sensing, in situ observations, crowd sourcing, citizen scientists and are distributed over many databases. The data are variable quality, temporal and spatial coverage and resolution, accessibility, and usability.

- The link between data and information and action are very limited and there is an urgent need for improvements. Concepts ranging from distributed and centralized platforms to a digital ecosystem are being considered.

The participatory sessions further developed the draft road map that resulted from the first workshop in 2018. Besides reaching a consensus vision for 2025, road map elements for the next six months were collected concenring community building and organization, finances, strategy, external stakeholders, and content.

In a collaborative effort, input for a case study on “Reducing Plastics in the Ocean within a Growing Global Economy: Understanding the Data Needs to Inform Actions” was compiled for the following sections of the case study report: Introduction, Wicked Problem, Conceptual Model, Decision Space, Hazards, Vulnerabilities, Foresight, Interventions, and Recommendations. It was agreed to carry out this case study over the six months prior to the Third Workshop at the end of May 2020 both as a preparation for the workshop and as a community building effort.

ROADMAP

TBA

FOLLOW-UP CASE STUDY

TBA